Where the mind is without fear and / the head is held high / Where knowledge is free / Where the world has not been / broken up into fragments by / narrow domestic walls. — Rabindranath Tagore, 1901, excerpt translated from Bengali by Amartya Sen

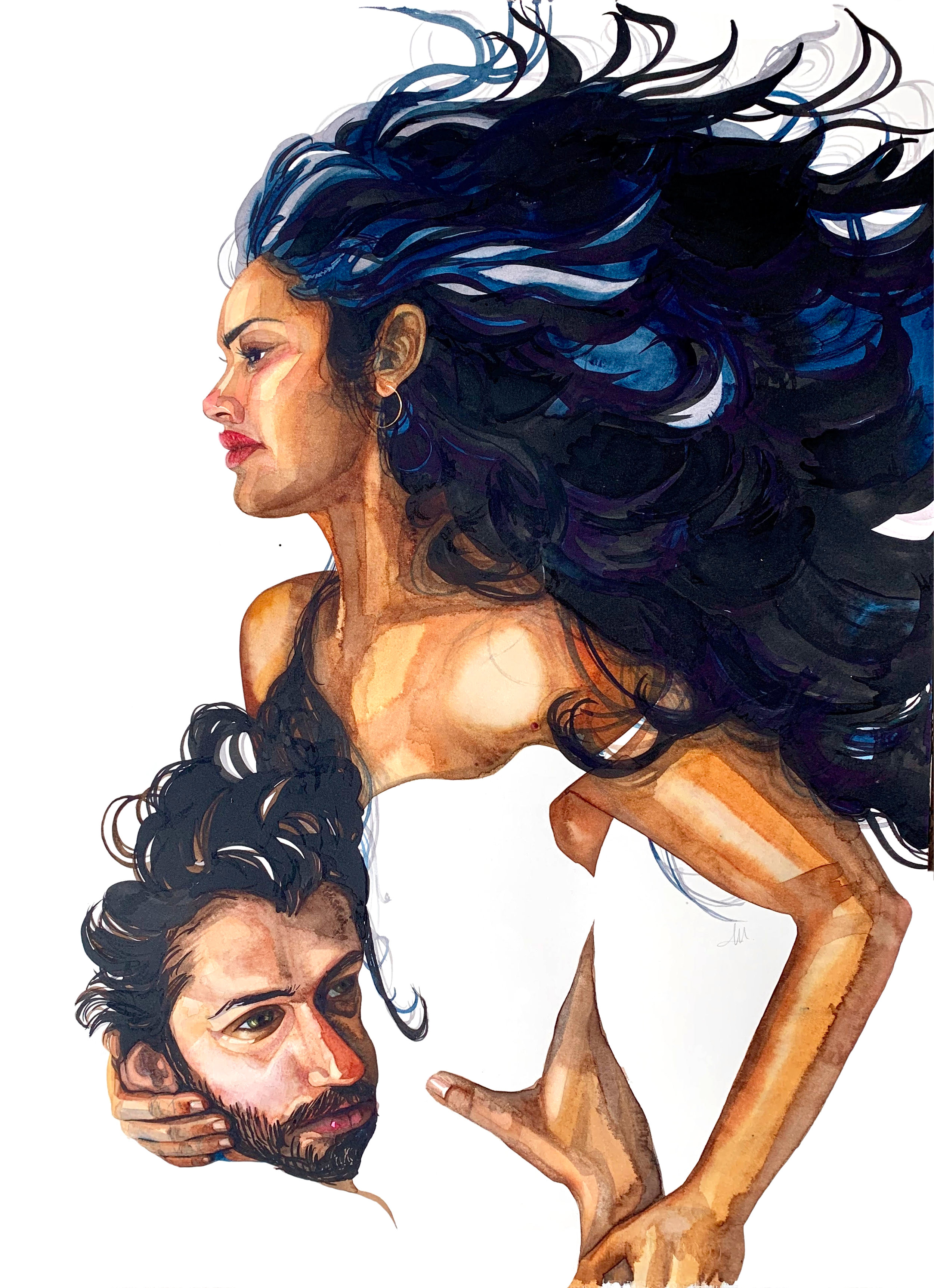

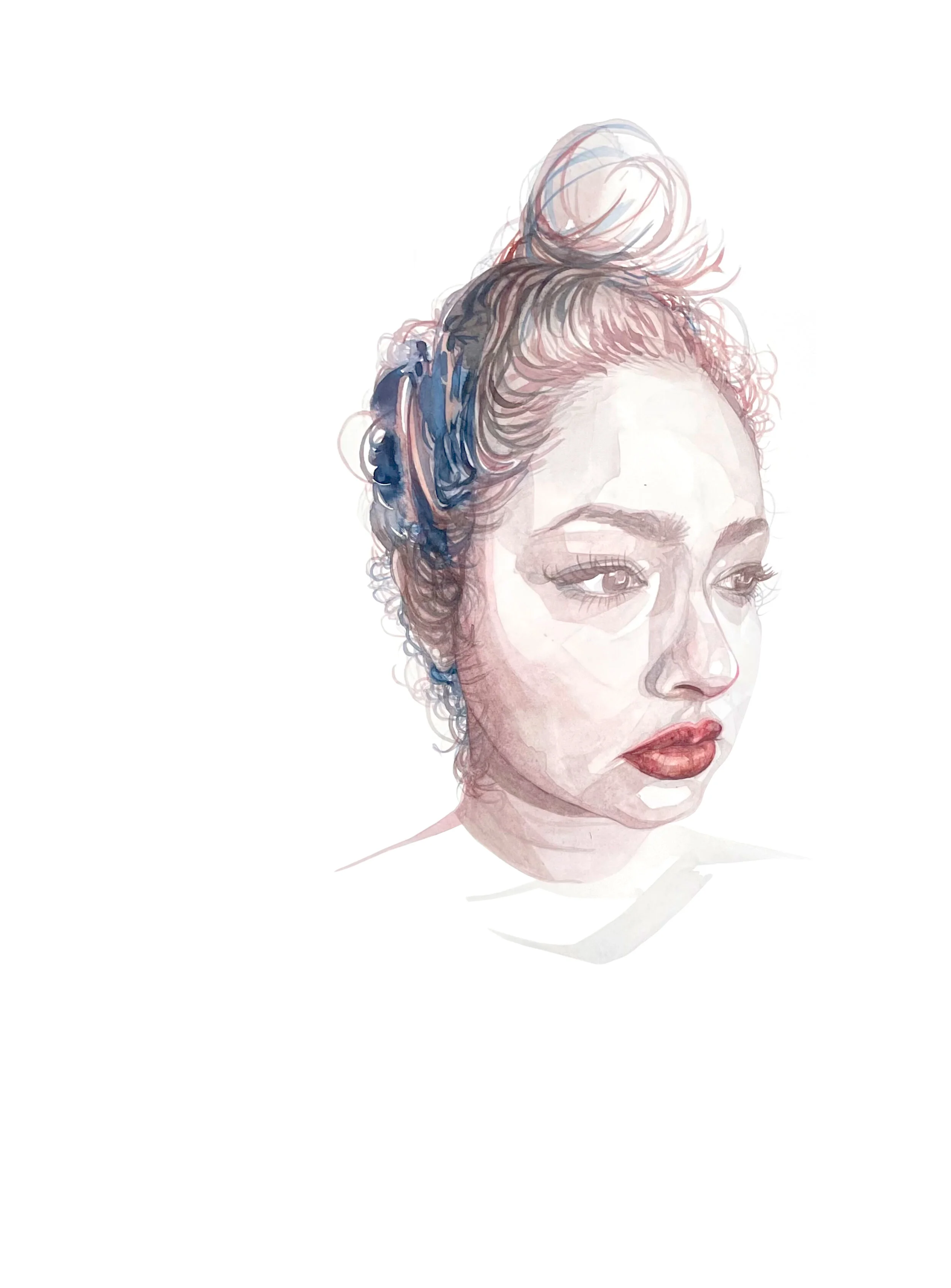

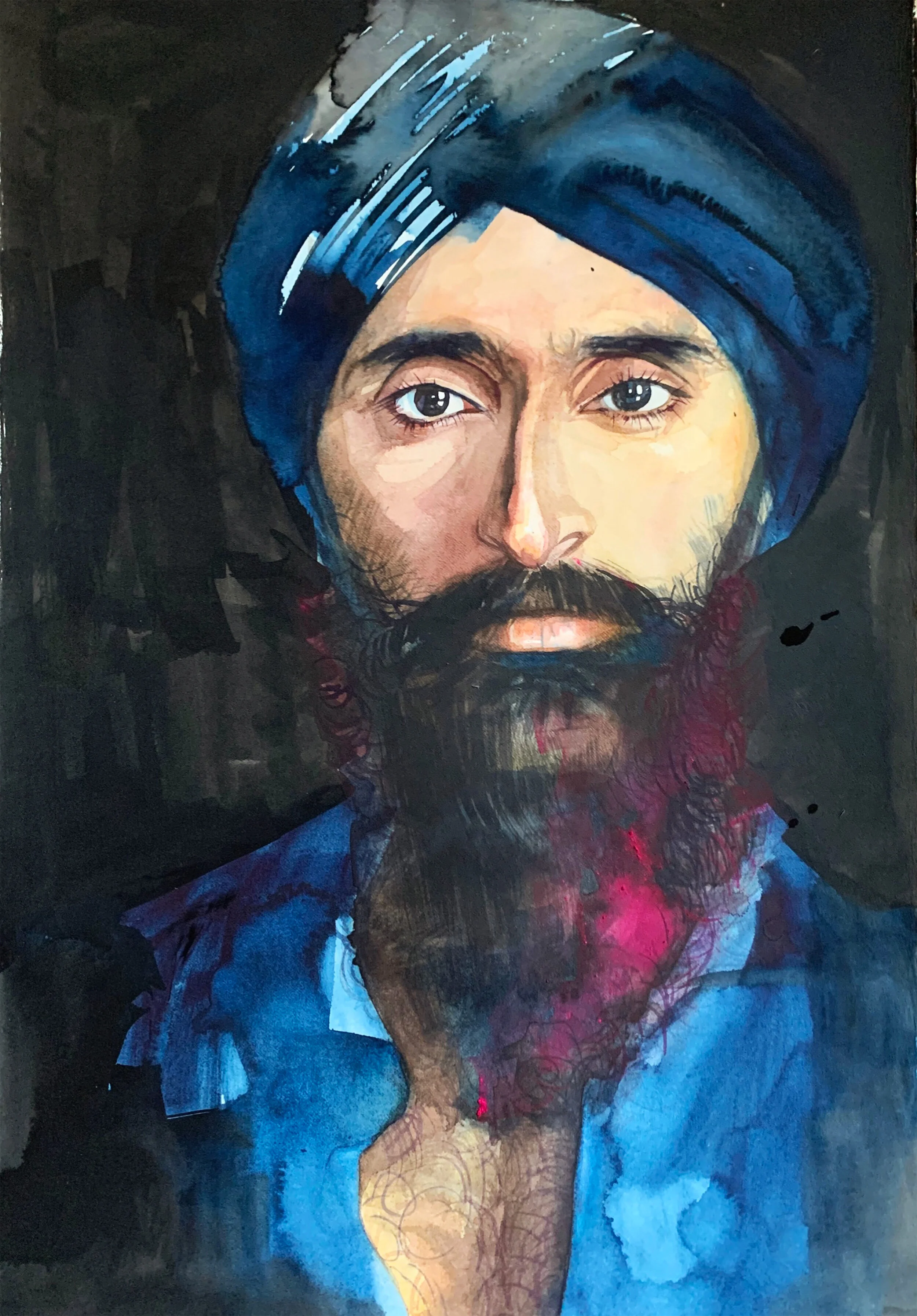

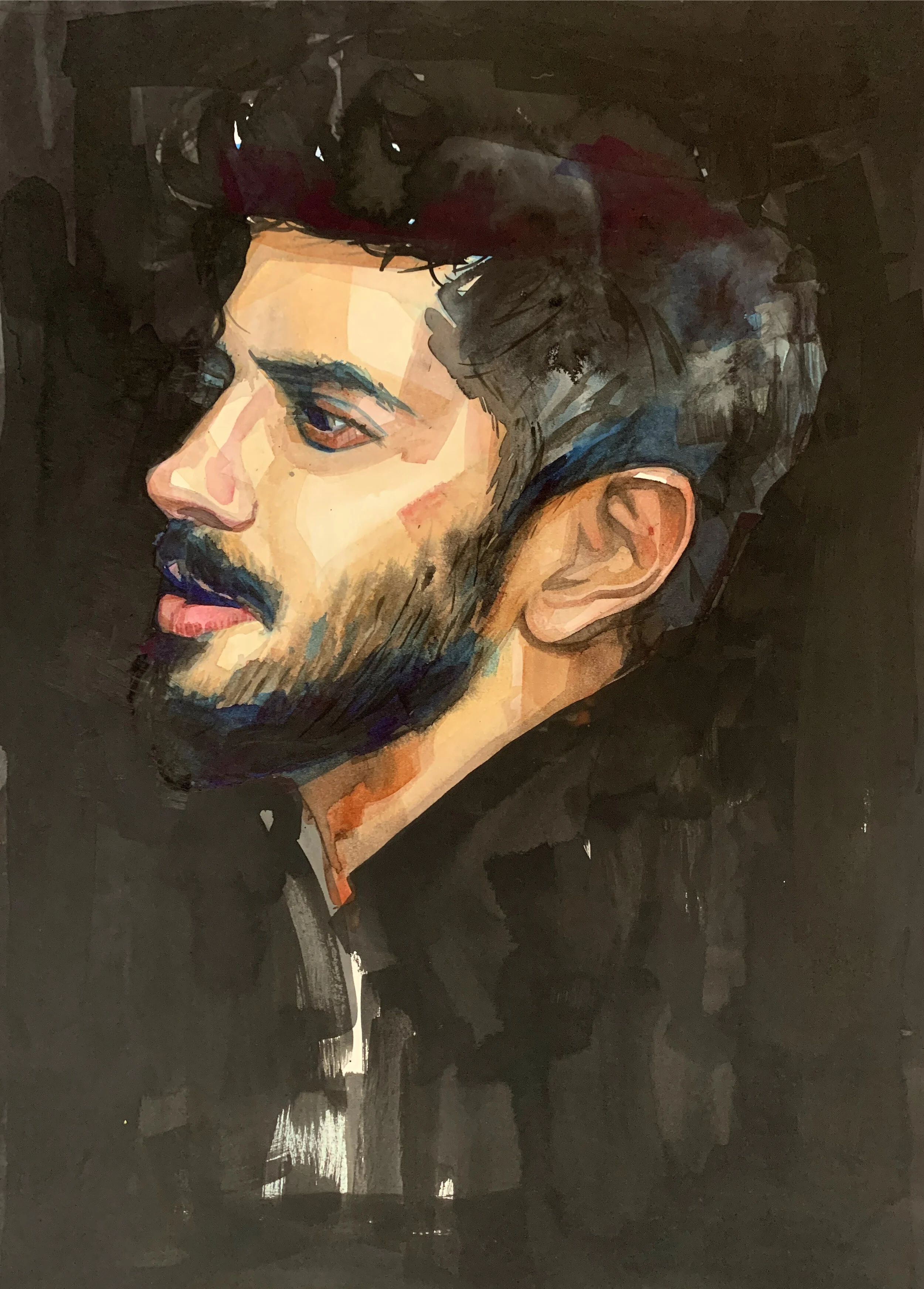

Artist’s Statement: The Sun Babes

Michelle Sindha Thomas

The art history I studied in early 00s America was notoriously absent of faces like mine. Historical images of faces like mine appeared only in a National Geographic sense, in an ethnographic context — making only occasional cameo, usually in a documentarian’s catalogue of conquered peoples and places. Artists from places like mine were presented as artisans, without individual whim or whimsy, marching to the tune of an ethnic collective consciousness. To conjure my despair, imagine a world in which text after text summarily represents the art of Europe in one chapter with an image by Fragonard, labelled only as “1700s, Central Europe, painting on linen”.

I rallied against the exclusion of people of color from the canon, taking Asian art history classes, studying current art from Africa, architectural commissions of the Mughal emperors, begging instructors for independent-study courses on subjects not offered, making pilgrimages to design districts in Hong Kong, Singapore, Kochi, more, more, more, a hungry clawing for all that had been withheld.

I made lots of work in response to these learnings, culminating in a senior project: A huge self-portrait in the style of Diego Rivera, carrying on my back a legion of Indian stereotypes, entitled, Indiahibition: A Billion Chips on My Shoulder.

My portfolio is overwhelmingly figurative because my urge to make comes from an urge to communicate, to create meaning from chaos, to establish a structure on my own terms and according to my logic — and since my face has been absent from the canon, I make up for lost centuries and paint it again and again and again. I know that this work is not complete, because when I research the acquisitions of my city’s art museums, hoping to find work by an Indian-American artist, an Indian artist, or an artist of the diaspora, I come away sorely disappointed (When one local museum lately hosted a show called East Meets West: Jewels of the Maharajas, the catalogue consoled mainstream viewers by saying such magnificence was made possible by British “protection" and the Pax Brittanica.). So I make representations of those underrepresented I know and love so well: A family sitting together at an airport because airports are the sites of our reunions and our aching departures; a series of paintings called Elephant Eggs that reflect the immigrant’s child’s identity crisis, crises; a master’s thesis on how to read the art products of marginalized artists (with the same lens one would view other artists — the artist as independent visionary rather than ethnographic object), portraits upon portraits of girls like my sister, bold and brave, fiercely resilient, and never made the victim. I have some very specific things to say, and abstraction does not serve my purposes. I cannot suffice with color stories when I am not convinced anyone has yet put the precise words together to express my concerns.

Enough. It is such hard work providing context for the mainstream viewer ever-looming over my consciousness. It is emotionally taxing to create didactic work that puts on a face, trying so desperately to explain a multifaceted upbringing and a multifaceted identity to a firmly alien audience. It is like having chosen a love lacking in natural awareness and empathy, he needs you to spell out what you are feeling, explain your reactions to offense, over and over again. You see in his face that he does not completely grasp you. He will never feel that he can read you, your motivations, what happens next. He tells you, after the novelty has worn off, after lots of crying and failed attempts at communication, that you remain elusive, that he doesn’t know you.

Is it possible to shut out the world and make art that can take off its bra and relax, that is quiet and simple, and doesn't have to code switch? As an adult, I have never given myself the chance to make work for just me, not representing people of color or Indian-Americans, or women, or early millennials, or artists, or educators, or Midwesterners, or Christians with roots in Kerala, hundreds of millions of us with the incongruous surname Thomas. I can’t carry everyone anymore, and I’m fed up explaining myself to strangers, labelling myself for easy comprehension, digestion, categorization, discrimination.

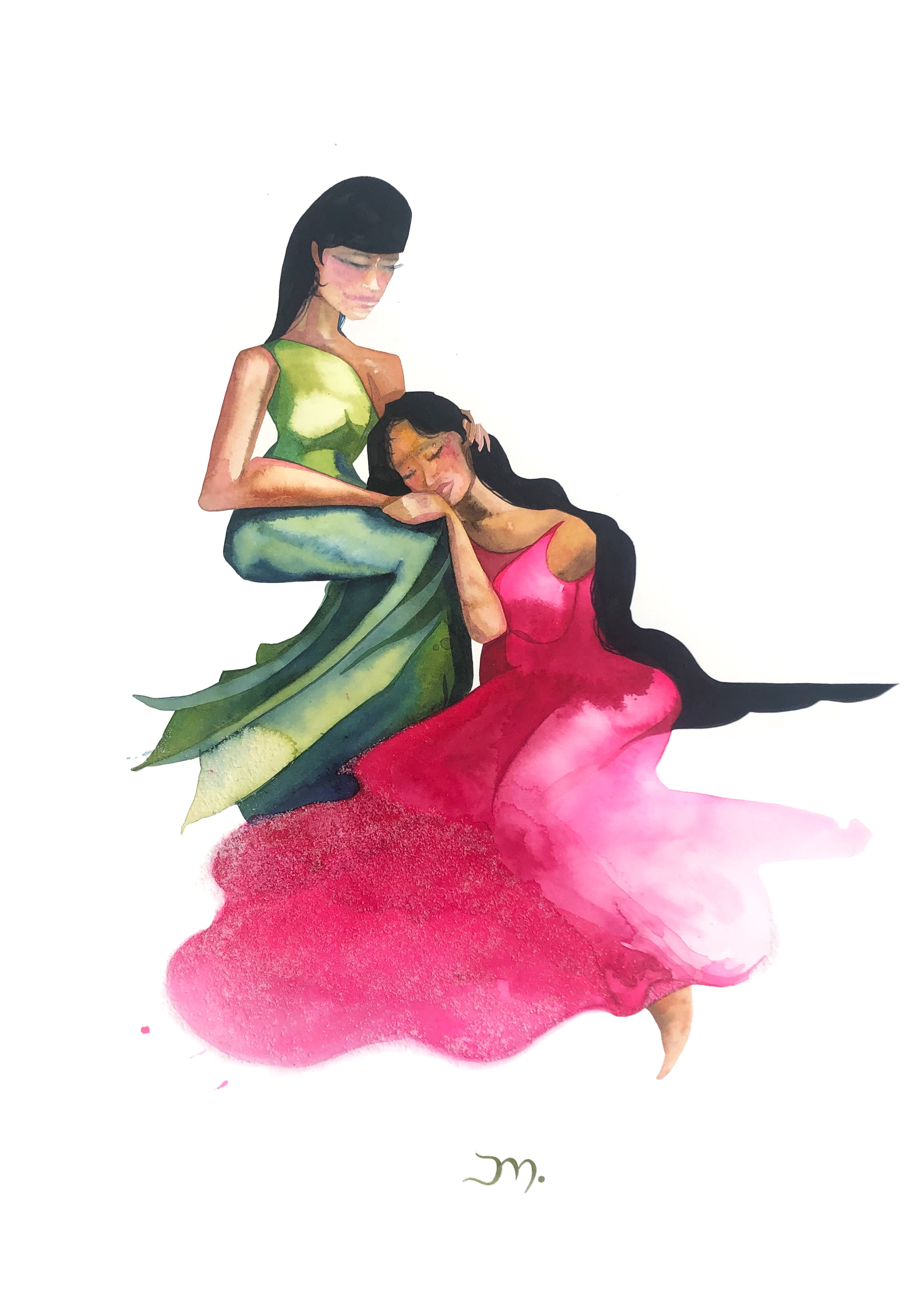

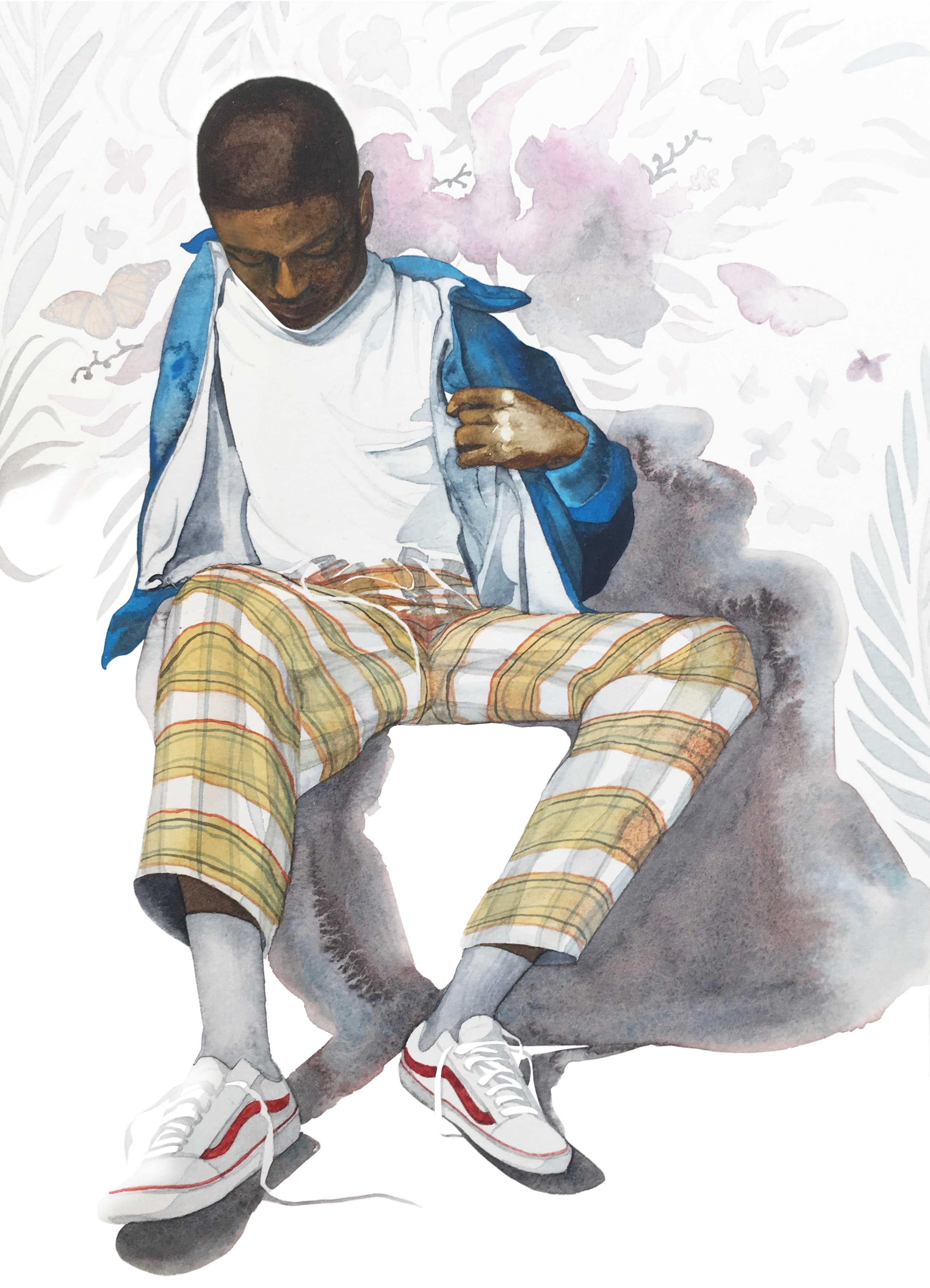

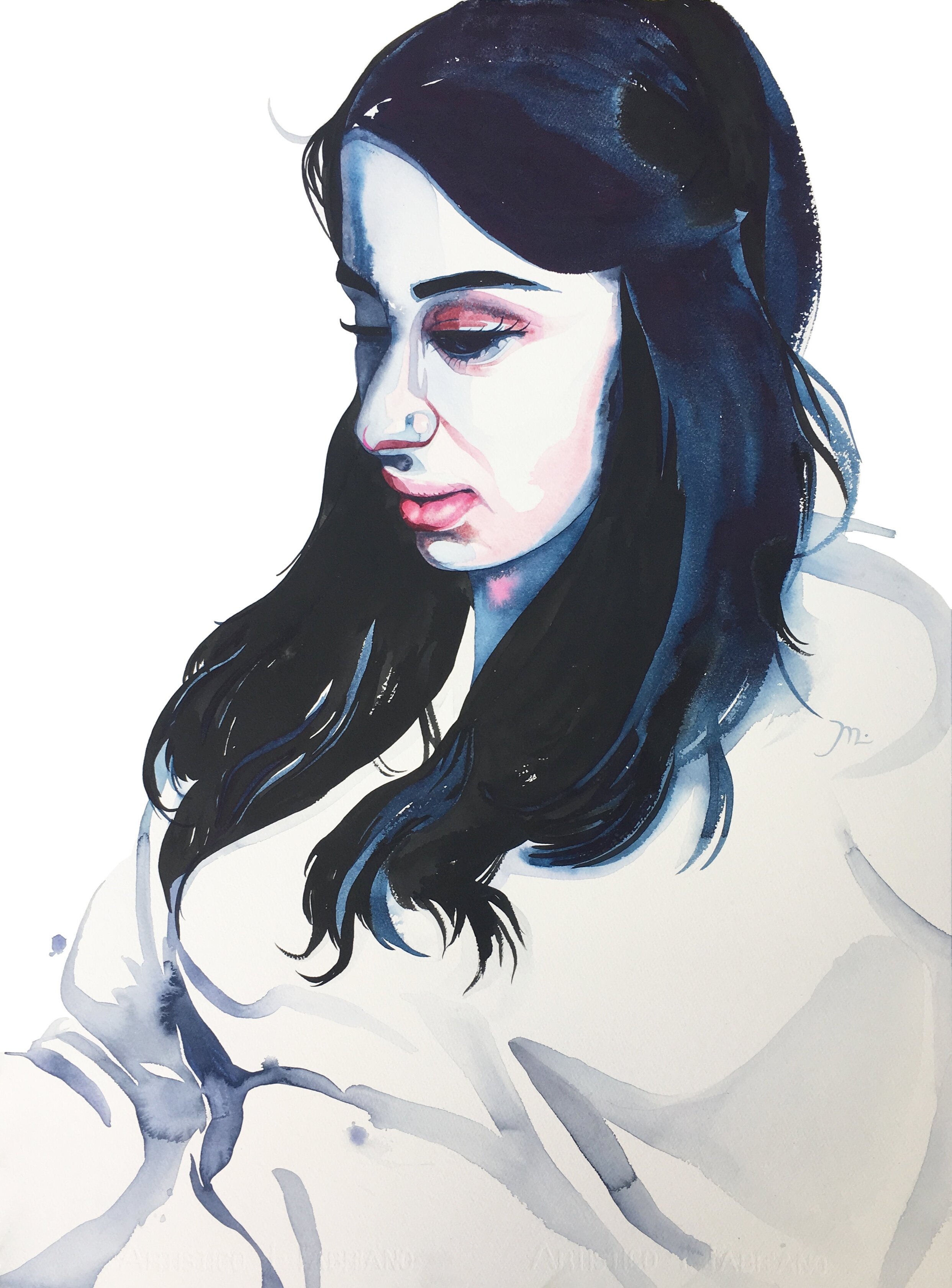

The Sun Babes are ethnographic objects at rest. They are alone, deliciously alone, as I am when I close the door, take off my shoes, find a sunny spot, and sit in perfect silence.

I do often feel alone in my worldview — I’ve made a gang to keep me company. The Sun Babes are lighthearted, they are gentle, they do not argue.

They have no discernible past, offer no context and few clues as to their background, time and place and future. They give no explanation for their attitude, the unexpected texture of their hair, their accent, their religion, their height, their weight, their taste in music, their education, their handwriting, their racial ambiguity, the contents of their suitcase, their resting face. They are drinking up nature; their very names mean sun, light, gold. Alone at last, they are at ease and without obligation; they are free.